Times Supermarket Co-Founders Recall Herman’s Dream

By: Karleen Chinen

It is 9 a.m. on a cool Tuesday morning. The foot traffic into Times Super Market’s Kahala store is beginning to pick up. Shoppers stroll through the doors, oblivious to the bronze plaque secured to the right-hand wall at the store’s entrance- obscured slightly by kiddie rides and bubble gum machines.

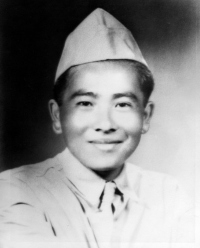

The plaque reads simply: “Dedicated in Memory of Herman T. Teruya, Sergeant, U.S.A., 19191944.”

“Eventually, I’m going to have a new one put up, with more information,” says Wallace Teruya, vice chairman of Times Super Market. Besides providing more information about his younger brother, his service to America as a member of the 100th Infantry Battalion, and how he died in World War II, Wallace would like the new plaque to capture Herman’s entrepreneurial spirit.

He was a groceryman at heart,” explained Wallace. His older brother, Albert, Times co-founder and senior vice chairman, concurs. Had Ushi and Kame Teruya’s third son come home from the war, he would have thrown his heart and soul into what is today, one of Hawaii’s largest and most successful family enterprises, Times Super Market, Ltd.

But the war took Sgt. Herman Takeyoshi Teruya’s life three months before his 25th birthday. He died in the battle for Monte Cassino on January 25, 1944.

Who was this bright young man–so fascinated by the business of retailing?

He was the child of immigrants. Ushi and Kame Teruya immigrated from Okinawa in the early 1900s and settled on the Big Island’s Hamakua coast where they worked for the sugar plantation before becoming independent sugar growers. The couple had six children-four boys and two girls.

Albert was the first to leave the Big Island to work in Honolulu. That was 1929. Wallace followed a year later, and the rest of the family moved to Honolulu in 1933. They lived in the Kapiolani district, where the Holiday Mart store is now located. Albert recalls that the area was swamp land where many people farmed.

In 1935, when Herman was just 16 years old, the three brothers opened a small soda fountain in downtown Honolulu. While a student at McKinley High School, from which he graduated in 1938, Herman would rush home after school and gather up vegetables and eggs his parents had raised. “He used to go around to the neighbors, selling eggs, lettuce and green onion. He had a goal already. He was an entrepreneur; he liked selling,” said Wallace.

In the morning, he sold newspapers. “On Sundays, he tried to teach our younger brother, Robert, how to sell newspapers- where to sell papers on Kalakaua Avenue in Waikiki. He selected a strategic location, and told Robert, ‘This is a good place; you stay here and sell.’”

Herman also worked at the Aoki Store in Waikiki, and ironically, for what is today one of Times Super Market’s friendly competitors, Star Market. At the time, Star had several small stores. He also helped out at the family’s restaurant, Times Grill, which the Teruyas ran from 1939 until early 1947.

On Sundays, the brothers would go out carousing with Herman-playing tennis or baseball.

Herman was an enterprising and observant young man who always gravitated towards opportunities to learn something new. When he wanted to learn the meat-cutting trade, he went to work at the Palace Meat Market, a German-owned business located at Beretania and Keeaumoku streets.

He also made the rounds of nearby Caucasian families, offering to do their yard work. And if he found that he couldn’t continue working for the family, he’d find a replacement and train them.

As a child, Herman was especially close to his oldest brother, Albert. He was a thoughtful child. “On his own, without being told, he’d do things my father or mother wanted.” said Wallace. He says he saw that thoughtfulness even after his brothers had been drafted and were stationed at Schofield. “On weekends, he used to come home. Herman would wash his uniform at Schofield and bring it home for my mother to iron. But him,” laughed Albert, pointing to Wallace, “he brings the whole uniform home to be washed.”

Although Herman was generally on the quiet side, Albert says he had no trouble expressing himself when he needed to.

Herman’s dream was to open his own store, and he wanted Albert and Wallace to be his partners. “If we didn’t go along with him, he was going to do it himself, because he wasn’t interested in the restaurant business,” explained Wallace.

In November 1941 both Wallace and Herman were drafted. Early on, their parents weren’t overly concerned that two of their sons had been drafted. America wasn’t at war at the time, and besides, their sons were stationed in Hawaii. “Even when our 1000h Battalion was shipped out to the Mainland, I don’t think my parents were worried. But when we went overseas and started contacting the enemy and there were casualties, then they started worrying.” The casualty reports were published in the Japanese language newspapers and broadcast over the radio.

Herman’s entrepreneurial spirit never died-not even when the 100th was in training at Camp McCoy. Wallace recalls that Herman spent his furloughs visiting stores and super markets, studying their operations. “On weekends, he would go downtown with the boys to eat. He used to recommend to the boys what type of steak to order,” laughed Wallace.

Wallace and Herman were both assigned to Dog Company, initially. Wallace was later transferred to Headquarters, while Herman remained with Dog. Both wrote home-Wallace more often to his fiancee, and Herman to his parents via Albert. “He wrote about where they went, what they did on their furlough, interesting things. He was always thinking about our parents and us-the family, telling us not to worry.” That’s how Herman closed all of his letters. Their parents looked forward to letters from their soldier sons, and always asked Albert whether there was any news pertaining to them.

In January 1944, the 100th ran head-on up against the Germans in the battle for Monte Cassino, the strategic mountaintop monastery, which the Germans occupied. The brothers had been separated, although there was nothing unusual about that. Wallace was in the rears with the kitchen crew. The last time he had seen his younger brother was during a rest period about three weeks earlier.

On January 25, 1944, Herman-by then a sergeant-was selected to direct the firing of heavy artillery mortars for the infantry, explained Sgt. Conrad Tsukayama of Dog Company. He described the battle for Cassino as a “suicide mission.”

Tsukayama had gotten to know Wallace and Herman when they belonged to the 298th Infantry of the Hawaii National Guard. The three had dug gun positions for heavy weapons posts along the Windward coast, from Waikane to Waimanalo, in the days following the attack on Pearl Harbor. “When we joined up, we didn’t know each other very well. But after a while we’d talk story about our feelings, about our country … He had a dream, even at that young age, that he was going to come back and open up a store,” recalled Tsukayama.

He said Herman and two other observers were in an abandoned farmhouse relaying information to the infantry by telephone line when the Germans shelled the structure, killing everyone. When Tsukayama learned that Herman had been killed, be remembered Herman’s dream.

Herman Teruya would never open his own store.

Communications were apparently poor. Several days passed before Wallace learned that his brother bad been killed. “I didn’t know he was killed. But one day, Kenneth Mitsunaga (of Dog Company) came by. He told me, ‘You heard about it? “What?” asked Wallace. “Ey, your brother got killed, you know.” Wallace was stunned. He broke down in tears and cried.

Back in Hawaii, military officials bearing a flag, came to the Teruya home to inform them that Herman had been killed in action. “The door bell rang, so I went downstairs to answer it.” The dreaded task of breaking the sad news to his parents fell on Albert’s shoulders.

He paused for a few minutes, trying to figure out how to tell his mother that one of her sons would not be coming home alive. “I was wondering how to tell them. And yet, I had to let her know. I waited a little while and then when I was sure she was in good condition and sitting down, I told her.

“For a while she couldn’t believe; she couldn’t believe that he got killed. ‘Is that really true? Really true?’ she kept asking. The family gathered in the living room and prayed and cried together,” recalled Albert. “They were so sad, crying. It really shocked them. It was always something they had heard about other families’ sons.” He says he’ll never forget the loss that was written all over their faces.

Herman’s body was not returned to the Teruyas until April 1949. The family held a memorial service at Schofield Barracks on May 4, 1949 and laid him to rest at Punchbowl National Cemetery.

Time eventually healed the pain of the family’s loss.

Wallace returned safely home from the war. After toying with the idea of opening a variety store, he and Albert nixed it and decided to use the experience they had gained in the restaurant business and expand it into a full-on market operation. Albert concedes that Herman’s dream of opening a market played a part in their decision to open a market instead of a variety store. That year, the year Herman came home, Albert and Wallace Teruya-along with their cousin, Kame Uyehara opened the first Times Super Market in McCully.

In 1956 they opened their second store, in Waialae-Kahala, which they dedicated to Herman. “We went into the market business because of him,” explained Albert. “When we put the plaque up there, we felt much better- that he knew we remembered him.” The plaque was their way of showing Herman how much they appreciated the ideas and dreams he had shared with them.

Ushi and Kame Teruya were proud of the tribute Albert and Wallace were paying to their brother. “When they were alive, I took both of them to see the plaque,” recalled Albert. There are moments when Albert and Wallace can’t help but languish at how Times Super Market might have been different had Herman come home alive. “I wonder sometimes what his plan would have been if he was with us,” Wallace wonders sometime. “Would it have been different from what we’re doing now? When I go to his grave, I always thank him for the idea for the market.”

“I know this is impossible, but I can’t help but think about how good it would have been when he came back and put his ideas into practice,” said Albert. “I’m sure he would have been successful. I always think about how thoughtful he was, the things he did. Even though he was younger he taught us many good things.”

Almost 50 years have passed since Herman died-although it doesn’t feel like 50 years, says Albert. “I still think it’s not that long-because we have his picture, his Purple Heart and a message from the President.”

When Albert’s second grandson, Corey, was born, son Elton and daughter-in-law Jodell asked Albert to select a Japanese middle name for their son. Albert chose “Takeyoshi”-Herman’s middle name. He’ll be visiting Corey on the Mainland this summer. “Since I’m going over, maybe I’ll talk to him about Herman …”

This article appeared in the June 19, 1992 issue commemorating the 50th anniversary of the formation of the 100th Infantry Battalion. It has been reprinted courtesy of The Hawaii Herald, Hawaii’s Japanese American Journal.