One For All — and All For One

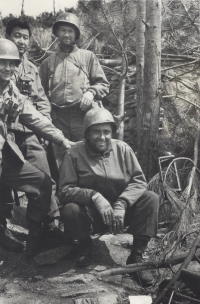

In October 1943, a 27-year-old U.S. Army chaplain of German descent from Pennsylvania was sent to the 100th Infantry Battalion as a replacement. The 100th was fighting in Italy when Chaplain Israel Yost joined the unit. He was initially shocked to find that the unit was very different from his 109th Engineer Battalion of the 34th Infantry Division to which he had first been assigned. Many of the men were German Lutherans like him. In contrast, the men in the 100th were primarily Americans of Japanese ancestry (AJAs) from Hawaii, and most were Buddhists. But the Lutheran chaplain was undeterred.

Working with the 100th’s morale officer, Captain Katsumi Kometani, a dentist by profession, he accompanied the men through some of the most brutal battles of the war. His experience affected him deeply and strengthened his commitment to tend to the needs of others, fight racism, and work for social justice as a pastor following the war.

Born in 1916, Israel Yost was the third child of a deeply religious Pennsylvania Dutch family who lived in Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania. Young Israel was only 9 years old when his father, a farmer who supplemented the family income as a salesman of farm equipment, was killed in a tragic auto accident. With his passing, the farm had to be sold. Israel’s mother opened a butcher shop to provide for her family. The business did not do well, however, and his mother was forced to close the shop a year later.

Israel’s mother remarried a short time later and the family moved to Phoenix, a small town located outside of Philadelphia. Attending high school there, Israel soon found that his Pennsylvania Dutch accent marked him as an “outsider” among the other students. In spite of the isolation he felt, Israel was an outstanding athlete. Years later, his physical stamina would help him make it through the war.

The tragedy of his youth — losing his father at such a young age, his family’s poverty and the discrimination he felt — left a lasting impression on young Israel and inspired him to enter the ministry in order to help alleviate the suffering of others. In 1933, he skipped his senior year of high school and was admitted to Muhlenberg College, a small Lutheran Church-affiliated liberal arts college. He was awarded a scholarship, graduated in four years and then enrolled at the Lutheran Theological Seminary in Philadelphia, from which he graduated in 1940.

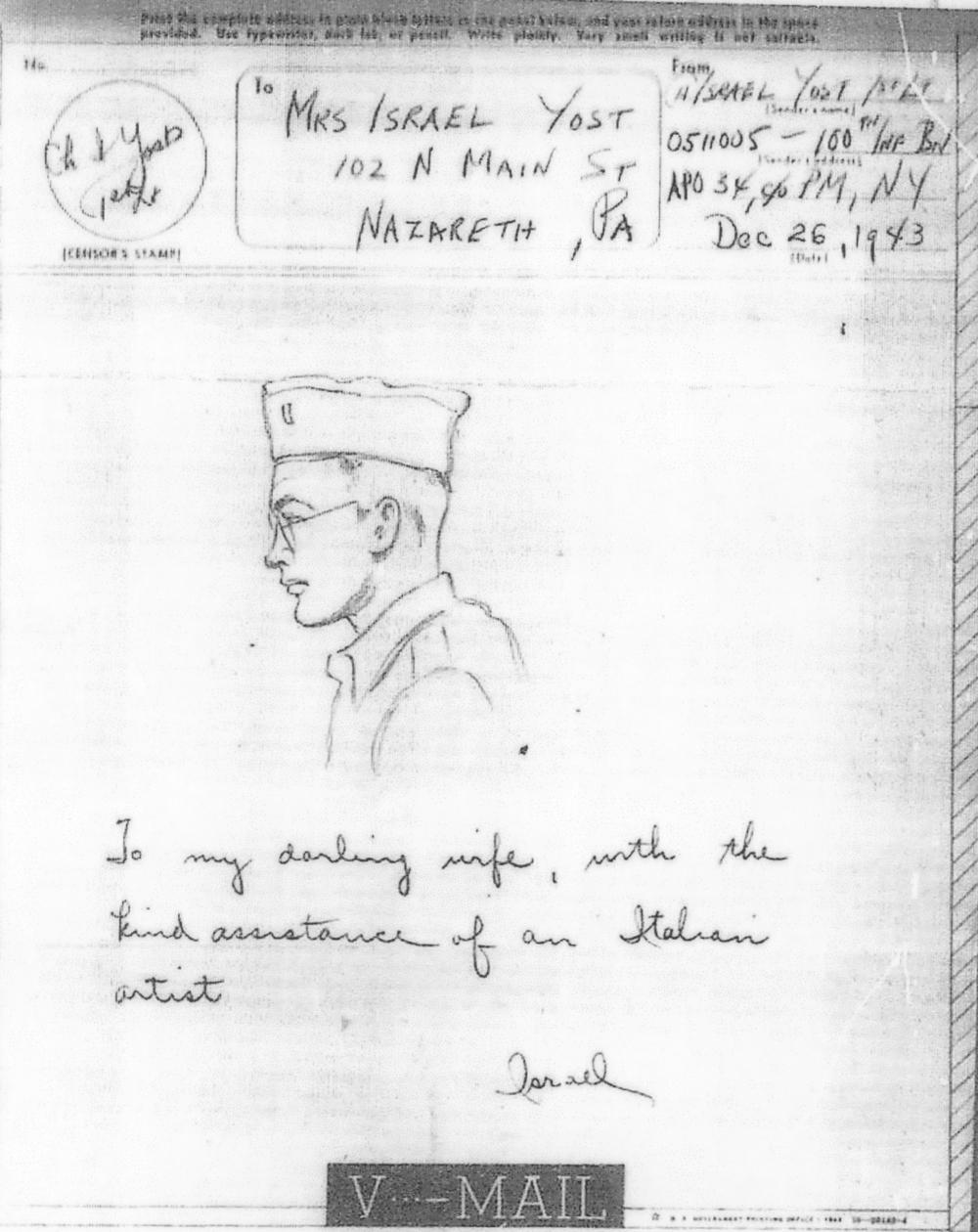

Yost was ordained a Lutheran pastor and assigned to two small rural congregations in Pennsylvania’s Lehigh Valley. There he met and married Peggy Virginia Landon, the daughter of a Chesapeake Bay fisherman and a member of his congregation. They soon had a daughter, Monica, and settled into what he hoped would be a happy and fulfilling life.

However, the outbreak of World War II left Yost feeling a great need to help in the effort as a military chaplain. He trained at the U.S. Army Chaplain School at Harvard and was temporarily assigned to the 109th Engineer Battalion until a position opened up in a combat unit. When he arrived in Italy, however, he was reassigned to the 100th Infantry Battalion, which had arrived in Salerno in September 1943.

Yost quickly learned that the U.S. Army, which was overwhelmingly Christian, had no provisions in place for soldiers of the Buddhist or Shinto faith. One of his first tasks was to hold a memorial service for Sergeant Shigeo Takata and Private Keichi Tanaka, both of whom were killed in action on September 29, 1943, just hours apart and only days after entering battle. They were the first 100th Battalion soldiers to die in battle.

Typical of his period of adjustment after joining the battalion was this statement by Captain Jack Mizuha, who asked him to help his men: “Chaplain, I don’t believe the same things you do, but my men want a memorial service for their buddy, and I want them to have it. Just go ahead and I’ll listen.”

In time, the differences disappeared and he was befriended by Katsumi Kometani, who served as the 100th’s morale officer. Yost settled into a routine, helping the men at the aid stations, conducting Lutheran services and following the stretcher bearers onto the battlefield to help retrieve the wounded.

As the 100th fought across Italy and participated in the battle for Monte Cassino, the mountaintop monastery that had been overtaken by the enemy, the casualties mounted. It fell to Yost to collect the bodies of the dead, register their names and prepare their bodies for burial and trans-shipment. He worked side-by-side with the men of the 100th through their worst combat missions in Italy and France, narrowly missing death several times. On one occasion, he even set off a mine, injuring a soldier with him. Another time, the jeep he was riding in was bracketed by enemy fire. The men scolded him constantly for taking chances on the battlefield, when he would go out to see them in their foxholes. However, many expressed appreciation for his willingness to share in their suffering.

Perhaps his hardest role was holding the hands of the young men, praying for them as they lay dying in the aid stations. He bore this task without complaint, just as he did writing letters of condolences to their families.

The soldiers would come to him for advice: One soldier asked Yost how he could forgive a wife whom he loved very much, but who had been unfaithful to him and had given birth to a baby by another man. He said he did not know the answer, as many of the men had been away for three years — he asked him to forgive her. There was also the issue of men with wives in Hawaii who fell in love with girls in Italy and France. The world for these young men grew increasingly complex. One asked him how he could kill as a soldier and yet remain moral. Yost acknowledged that he faced the same inner conflict, explaining his concern that being an Army chaplain provided a moral sanction for killing.

Yost appreciated the soldiers’ complete acceptance of him, perhaps because they knew that what they told him would likely never come back to Hawaii. He was pleased that they did not think of him as a haole (colloquial term for whites in Hawaii).

In June 1944, the 442nd Regimental Combat Team entered battle in Europe. Two AJA chaplains — Masao Yamada and Hiro Higuchi — were assigned to the regiment. The 100th Battalion was subsequently merged with the 442nd, becoming the combat team’s 1st Battalion, although it was allowed to retain its name. Chaplain Yost, who by then had developed a bond with the men, realized that he might be transferred out of the 100th, so he requested, and was granted, special permission to remain with the 100th.

In June 1944, the 442nd Regimental Combat Team entered battle in Europe. Two AJA chaplains — Masao Yamada and Hiro Higuchi — were assigned to the regiment. The 100th Battalion was subsequently merged with the 442nd, becoming the combat team’s 1st Battalion, although it was allowed to retain its name. Chaplain Yost, who by then had developed a bond with the men, realized that he might be transferred out of the 100th, so he requested, and was granted, special permission to remain with the 100th.

When the war ended, Yost returned to his family in Pennsylvania and put the war behind him, seeking out another rural Lutheran parish. He did, however, stay in contact with the now-veterans of the 100th.

![Chaplain Israel Yost [University of Hawaii JA Veterans' Collection] Chaplain Israel Yost [University of Hawaii JA Veterans' Collection]](https://www.100thbattalion.org/wp-content/gallery/veterans-chaplains/cache/yost_israel.jpg-nggid03464-ngg0dyn-200x0x100-00f0w010c011r110f110r010t010.jpg)

![Israel Yost, circa 1940s [University of Hawaii JA Veterans' Collection] Israel Yost, circa 1940s [University of Hawaii JA Veterans' Collection]](https://www.100thbattalion.org/wp-content/gallery/veterans-chaplains/cache/yost2.jpg-nggid03461-ngg0dyn-200x0x100-00f0w010c011r110f110r010t010.jpg)