Jack joined the Hawaii National Guard in 1939 and was promoted to first lieutenant in the 299th Infantry. When not working on the plantation, he was training his men. As a supervisor at a sugar plantation, which had been deemed an essential war industry by the government, he could easily have requested an exemption when the war broke out. But he would join the Army when called up.

Betsy returned to Hawaii a year later, but hadn’t told Jack that she was coming home. “I thought he had given up on me,” she recalls. But the “coconut wireless” never stops transmitting, and to her surprise, he was there to meet her on the tug when she arrived in Honolulu. They reconnected and then she went home to Kauai to see her family. Jack flew over the next weekend and asked her father if he could marry Betsy. “I don’t recall him asking me!” she says.

In 1942, Jack told Betsy that he would be training some of the new soldiers on Kauai. With three days notice, they were married in the old white church in Koloa. According to Betsy, one of Jack’s more imaginative methods for training new recruits was to take them hunting for wild pigs with dogs in the rugged mountains of Kauai. Jack believed that the excursions toughened up the men. All too soon the couple’s time together was over and on a few hours notice Jack shipped out with his men. Betsy and Jack were together on Kauai for only two months.

There were initially concerns about how the Army would find enough white officers to staff the new, predominantly Japanese American battalion and whether everyone would get along. But Jack was different from the other officers. He got along with the white officers as well as the Japanese officers and men, some of whom had been his classmates at UH. Jack went for training at Fort Benning, Georgia, and then was selected by Colonel Farrant Turner as training officer for the newly formed Hawaiian Provisional Infantry Battalion, which was renamed the 100th Infantry Battalion after it arrived in Oakland.

Betsy would join Jack, traveling from Kauai to San Francisco, then going across the country to Camp McCoy in Wisconsin, to Camp Shelby in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, and finally to Fort Benning, where he was required to take an officer’s course for captains. It was difficult to find housing, so they stayed in a series of apartments and rented rooms. But Betsy loved Jack and there was a sense that America was changing and that together they were breaking new social ground.

“Jack and I had small cocktail parties in Wisconsin for some of the officers once we found an apartment. They brought their ukuleles and whatever food and liquor they had,” says Betsy of her husband’s time in training. “I got to know several officers like Spark Matsunaga, Sakae Takahashi, Dr. (Katsumi) Kometani, Captain (Taro) Suzuki, and Alex McKenzie and his wife Roxanne, and we all went to parties together and became friendly. It was quite a bonding experience.”

“One day I was at a party and a Japanese officer came up to me and asked me to dance,” continued Betsy. “He said, ‘I never danced with a white girl before.’ I told him, ‘I never danced with a Japanese boy.’ Then we danced. I had never had a drink of sake before the parties.”

In July 1943, Betsy said good-bye to Jack as he shipped off to Oran, Algeria, not realizing she would never see him again. Jack was wounded in the leg on November 5 and could have stayed in the hospital. But by this time he had been promoted to major and named executive officer. He found a way to get out of the hospital and rejoin the battalion. In January 1944, the men of the 100th were part of the Allied forces ordered to attack Monte Cassino. Jack was fatally wounded and was buried at the American Military Cemetery in Nettuno, Italy. He was 29 years old.

In time Betsy realized that she would have to get on with her life. She would later marry U.S. Navy Captain Alfred Toulon. They returned to Kauai in 1963 where they raised their four children.

After the war, Punahou School put up a brass plaque honoring Major Jack Johnson. The University of Hawaii also named one of its student dormitories after him. But a living memorial of Jack remains in Betsy’s heart. “I was always sorry he didn’t survive. He would have been a very good influence on Hawaii. Everybody liked him.”

— by Michael Markrich

Michael Markrich is a Honolulu-based researcher, writer and editor. During spring 2011, he spoke over the phone with Mrs. Toulon while she was at her Kauai home and later met her when she visited Honolulu.

On November 20, 2011, Johnson Hall was rededicated after a renovation. Mrs. Toulon and several veterans who served with Major Johnson attended the ceremony. Click here to view the University of Hawaii’s News Release.

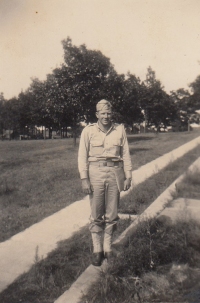

![Jack Johnson and Betsy in Kailua, April 1941 [Courtesy of Betsy Knudsen] Jack Johnson and Betsy in Kailua, April 1941 [Courtesy of Betsy Knudsen]](https://www.100thbattalion.org/wp-content/gallery/jack-johnson/cache/jackjohnson100191.jpg-nggid03791-ngg0dyn-200x0x100-00f0w010c011r110f110r010t010.jpg)